For the first decade or so after the discovery of the australopithecine A. africanus in 1924, it was widely assumed that there were only two early hominin lineages in South Africa, the other one being the somewhat later and heftier Paranthropus genus,represented by P. robustus. The fact that the fossil evidence from Sterkfontein and Makapansgat showed a wide range of sizes and features was put down to sexual dimorphism,age discrepancy or simply the continued evolution of a species over time. In 1948, Raymond Dart proposed that a new species, A. prometheus, be added in order to accommodate the fossil remains he had been examining from Makapansgat (MLD 1). The new taxon did not catch on, however, and was abandoned— for the time being, at any rate.

StW 573

Then, in 1994, Ronald J. Clarke a palaeoanthropologist at the University of Witwatersrand examined a box of fossil remains that had been recovered several years earlier from the Silberberg Grotto at  Sterkfontein. Within the box were four articulated foot bones (left) belonging to an early hominin (StW 573) that had been labelled as ‘Cercopithecoids’ (Old World monkeys). But that designation was clearly wrong, as the foot, when closely examined, turned out to be better suited to bipedal walking than climbing— at least when compared to apes and earlier australopithecines.

Sterkfontein. Within the box were four articulated foot bones (left) belonging to an early hominin (StW 573) that had been labelled as ‘Cercopithecoids’ (Old World monkeys). But that designation was clearly wrong, as the foot, when closely examined, turned out to be better suited to bipedal walking than climbing— at least when compared to apes and earlier australopithecines.

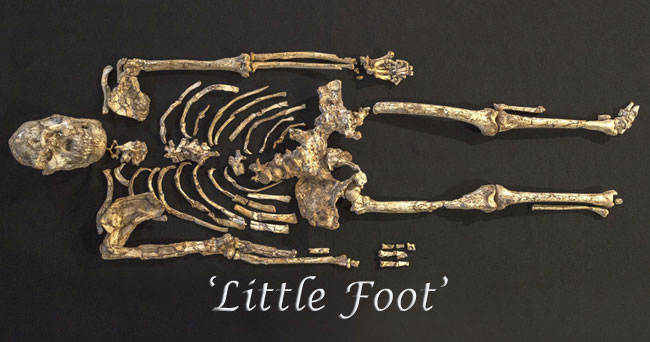

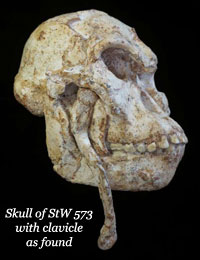

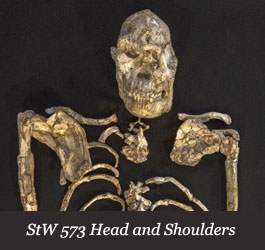

Clarke along with Philip Tobias, a colleague at Witwatersrand, organised a series of long-term excavations at the site. The work was slow and very laborious due to the nature of the matrix in which the fossils were embedded. This was made up of hard breccias formed from material that had flowed into the cave over the hundreds of thousands of years since it first appeared. But by 2017 they had recovered almost the entire skeleton (90%) of an australopithecine who they named ‘Little Foot’. Miraculously, these were largely undisturbed, apart from the effects of geological forces that have caused some distortion to one degree or another. One of the clavicles, for example, was found embedded in the right cheek (see photo below). The body elements that proved most difficult to extract have been the pelvis, which had been badly crushed, and the dentition, which required a lot of very delicate work. The final reconstruction of both still awaits. The remains have been interpreted as those of an older female, perhaps about 1.2-1.3 metres tall, with a small brain (similar in size of that of A. africanus) and lower limbs that were longer than the upper. Like all other australopithecines, there was a mix of apelike and human features. For example, while the ‘arms’ were still adapted for an arboreal lifestyle, the ‘legs’ were becoming more suited to bipedal locomotion.

The nature of the deposit (specifically, the lack of volcanic layers) also means that assigning a date to StW 573 has proved to be a major stumbling block in the interpretation of the remains and there is still quite some debate on the matter. It is important to know whether Little Foot was a contemporary, a successor, or a predecessor of A. africanus. The finds were initially given a date, on the basis of its stratigraphic position and the associated fauna, of something in the range of 3.5 to 3 million years ago, but this was contradicted by a radiometric date based on Uranium 238/Lead 206, that produced one of 2.2 million BP. Finally, in 2019 the breccia in which the fossil was found was dated (using cosmogenic nuclides Aluminum-26 and Beryllium-10 to around 3.67 million BP which, if correct, would make it the oldest South African australopithecine so far recovered by nearly half a million years.

block in the interpretation of the remains and there is still quite some debate on the matter. It is important to know whether Little Foot was a contemporary, a successor, or a predecessor of A. africanus. The finds were initially given a date, on the basis of its stratigraphic position and the associated fauna, of something in the range of 3.5 to 3 million years ago, but this was contradicted by a radiometric date based on Uranium 238/Lead 206, that produced one of 2.2 million BP. Finally, in 2019 the breccia in which the fossil was found was dated (using cosmogenic nuclides Aluminum-26 and Beryllium-10 to around 3.67 million BP which, if correct, would make it the oldest South African australopithecine so far recovered by nearly half a million years.

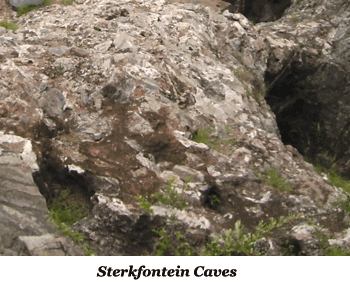

The terrain around Sterkfontein consists of rocky hills carved by river valleys and it was undoubtedly much the same 4 million years ago. The animals that roamed these hills and valleys were similar if not identical to species found in Africa today—although they may not necessarily have survived in the High Veldt of South Africa. The fossil mammals recovered from Member 2 include the bovid Makapania broomi, an extinct browser/grazer that favoured open woodland and relied on permanent sources of water. The carnivore and cercopithecoid (monkey) population, which make up the majority of the mammals found, is comprised of species that are habitual climbers who spent some or most of their time in the trees.

Skull & Dentition

The cranium and the mandible were recovered complete, although somewhat distorted by geological forces. Exposing the teeth has turned out to be a delicate, time-consuming process and, as of 2021, was still incomplete. Along with other australopithecines, the skull retained  quite a few ‘primitive’ (ape-like) features such as the flat, receding forehead, the relatively small braincase and the prognathic (‘projecting’) lower face. Overall, its face has been described as being ‘dished’. In other words, the cheekbones project beyond the tip of a sunken nose, which is quite distinctive among early hominins. In addition, its eyes are more widely spaced and there is a distinct sagittal crest (a bony ridge running the length of the skull), something not found among A. africanus. The cranial sutures are fused which would indicate that the individual was well advanced in years.

quite a few ‘primitive’ (ape-like) features such as the flat, receding forehead, the relatively small braincase and the prognathic (‘projecting’) lower face. Overall, its face has been described as being ‘dished’. In other words, the cheekbones project beyond the tip of a sunken nose, which is quite distinctive among early hominins. In addition, its eyes are more widely spaced and there is a distinct sagittal crest (a bony ridge running the length of the skull), something not found among A. africanus. The cranial sutures are fused which would indicate that the individual was well advanced in years.

Dentition is the most common means of distinguishing species and, despite the fact that they have not yet been fully cleaned and studied, the teeth of Little Foot do show a number of features that distinguish them from later hominins. The front teeth (the incisors and canines) are considerably larger than ours and, as is normal among apes, there is a noticeable gap (diastema) between the upper incisors and canines to accommodate the lower canines. The cheek teeth are larger than those of A. africanus and the wear pattern is unusual in that the front teeth are more worn than the back—probably reflective of tackling a more challenging diet— fruits with tough outer husks, for example— with an outmoded dental array. The amount of wear is very heavy, another indication of advanced age.

Upper Body

The upper body has also survived almost entirely intact. The shoulder girdle was found to be in good condition, although one of the clavicles had been displaced and was found against the right cheek of the skull. One of the scapulae (shoulder blades) was found still articulated with the upper arm (humerus).  The right forearm (tibia and fibulae) had been crushed, probably before death, along with the right hand, but the other arm is reasonably intact, allowing its length to be calculated. Not all of the ribs and vertebrae have been recovered so far, so there is no final, comprehensive study of the torso, but it is complete enough to demonstrate that Little Foot, like most apes, had a narrow thoracic inlet (the opening at the top of the ribcage). The surviving clavicle was proportionally longer that that of any ape and had an S-shaped curve resembling that of humans more than gorillas or chimpanzees. This combination of narrow thoracic inlet and broad shoulders suggest a strong shoulder joint, very much suited for climbing. The scapula has a prominent ridge for the attachment of the strong arm muscles needed to support their weight when climbing or while suspended. The glenoid fossa, where the upper arm bone (humerus) attaches

The right forearm (tibia and fibulae) had been crushed, probably before death, along with the right hand, but the other arm is reasonably intact, allowing its length to be calculated. Not all of the ribs and vertebrae have been recovered so far, so there is no final, comprehensive study of the torso, but it is complete enough to demonstrate that Little Foot, like most apes, had a narrow thoracic inlet (the opening at the top of the ribcage). The surviving clavicle was proportionally longer that that of any ape and had an S-shaped curve resembling that of humans more than gorillas or chimpanzees. This combination of narrow thoracic inlet and broad shoulders suggest a strong shoulder joint, very much suited for climbing. The scapula has a prominent ridge for the attachment of the strong arm muscles needed to support their weight when climbing or while suspended. The glenoid fossa, where the upper arm bone (humerus) attaches  to the scapula is at an oblique angle, which helps maintain stability in the hanging position.

to the scapula is at an oblique angle, which helps maintain stability in the hanging position.

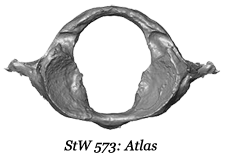

In this regard, the rare survival of the ‘atlas’, the upper cervical vertebra, was most fortunate. It is the main interface between the skull and the rest of the skeleton and is vital in keeping the head stable when it moves from side to side and up and down. The shape and orientation of the articular facets connecting the spine and the skull are more similar to those of chimpanzees, who are better able to look straight up, than humans.

As far as the ‘arms’ are concerned, despite having been crushed and deformed by injury, the right humerus is intact and was found in articulation at both ends, the shoulder and the elbow. The arm length (humerus + radius) is estimated at 53.4 cm, which is within the human range, but some of the details, such as the structure of the heads of the radius and ulna, are definitely apelike. The muscle markings indicate strong, flexible elbows and mobile shoulders, well-adapted for clambering about in the treetops. The bones of the hand are generally similar to those of modern humans, with shorter phalanges and metatarsals than apes but, as with most australopithecines. There was still some curvature in their fingers but this seems to have more to do with climbing than the sort of ‘knuckle-walking’ used by gorillas, chimpanzees and the rest of the apes.

Lower Body

The pelvis had been crushed post mortem and the various elements have been displaced by natural forces so that reconstruction is far from finished. The size and shape of the greater sciatic notch has been taken to indicate that Little Foot was female—the notch tends to be larger in human females than  in males. However, the comparative examples are rather thin and inconclusive.

in males. However, the comparative examples are rather thin and inconclusive.

Although the leg bones were broken, they were essentially recovered complete making it possible to calculate their total length at 61.5 cm, or a little over 8 cm longer than the arms, the reverse of what is ‘normal’ among apes. The ‘femoral head’ (the knob at the top of the femur) is large compared to A. africanus, but the neck is relatively short. The bicondylar angle (11°) indicates a valgus knee and therefore an upright posture. Only one foot has been recovered so far and that is missing its toes but it is clear from the angle of the first metatarsal that it had a prehensile hallux, a holdover from its ape ancestry.

In general, the construction of the foot was compatible with bipedalism but it appears that walking would have been slow and awkward. Running would have been out of the question and it is doubtful that they would have been able to cover any great distance, so it is doubtful if they ever moved very far from the trees. In fact, it is quite likely that their bipedalism developed through ‘hand-assisted’ movement along their branches rather than ambling along the ground.

Classification

When it comes to classification of material, archaeologists and palaeontologists tend to be either ‘lumpers’ or ‘splitters’. The former try their best to reduce the number of categories and are more accommodating when it comes to what they see as minor differences in an artefact type or animal species while the latter tend to subdivide. Initially, Clarke was unwilling to classify his discovery as anything more than Australopithecus but, as more and more of its morphology was revealed, he came to the conclusion that it was sufficiently distinct the species previously described (A. africanus and A. afarensis) to warrant its own designation. There were some similarities with the remains found at Makapansgat and proposed the revival of the term Australopithecus prometheus. The lumpers, on the other hand, have pointed out the wide variation found in the single species Homo sapiens (based on gender, age and race) and believe that what they see as minor distinctions are not enough to justify a separate classification.

Suggested Reading

| Ayala, F. J. and C. J. Cela-Conde | (2017) | Processes in Human Evolution. Second Edition |

| Beaudet, A. et al | (2020) | The atlas of StW 573 and the late emergence of human-like head mobility and brain metabolism. Nature. |

| Cartmill, M. & F.H. Smith | (2022) | The Human Lineage. Second Edition |

| Clarke R.J. | (2019) | Excavation, reconstruction and taphonomy of the StW 573 Australopithecus skeleton from Sterkfontein Caves, South Africa. Journal of Human Evolution |

| Clarke R.J. & K. Kuman | (2019) | The skull of StW 573, a 3.67 Ma Australopithecus skeleton from Sterkfontein Caves, South Africa. Journal of Human Evolution |

| Crompton, R. H., et al | (2021) | StW 573 Australopithecus prometheus: Its significance for an australopith Bauplan. Folia Primatologica |

| Owen-Smith, N. | (2021) | Only in Africa |

| Scarre, C. (edit.) | (2018) | The Human Past. Fourth Edition |