III. The Pliocene Epoch (c. 5.33-2.58 million BP):

The Pliocene Epoch saw some very important global developments that had a profound effect on the geography and ecology of Africa. The coming together of the Eurasian and African plates had closed off the Tethys Sea at its eastern end and now the same thing happened at its western end, at Gibraltar. The remnant, what became the Mediterranean, isolated from the world ocean, gradually began to dry out leading eventually to the desertification of the Sahara. In general, the forested areas shrunk and became more patchy with the areas in between occupied by grassland.

In East Africa the rift system of parallel valleys flanked by mountain ranges continued to grow and expand as tectonic activity in the region continued. The mountains of the Eastern Rift Shoulder altered rainfall patterns, effectively blocking the western monsoons and partially diverting the eastern monsoons towards India. The monsoons are the result of seasonal heating of the oceans and means that the rain is seasonal too. Diminished though it was, the amount of rainfall during the Pliocene was good deal more than it is today, with most of it falling on the mountain sides rather than the plain. In Kenya, which is right on the equator, the wettest months today are April and October, right after the equinoxes and the driest are February and August. Obviously, this affects the availability of food, especially for herbivores.

Veldt at Kruger National Park, South Africa

Survey results from the region have proven very informative as to its geology and ecology during the Pliocene. In the Afar, there are extensive deposits of alluvium, a mix of sand, silt and clay laid down by ancient rivers or washed down from the Ethiopian Plateau to the west, as well as lacustrine deposits associated with a large lake located to the east. The Eyasi Plateau, on the other hand, is made up of thick layers of volcanic tuff transported there by the prevailing winds, with little evidence of water-laid sediments.

In the Afar region, it has been possible to collect pollen samples, seeds and phytoliths such as silica, along with fossilized wood and leaves from securely dated contexts. The plants identified are pretty much the same as those found in other parts of the continent today but in areas receiving about double the rainfall currently received in the Afar. Much of the landscape can be characterized as typical open savannah, with various grasses dominating the pollen record but with expanses of bush and stands of .png) some of the hardier trees, such as acacia. Areas of forest are also documented. Samples taken from the former watercourses and the margins of the ancient lake include much more arboreal pollen, as much as 25%, indicating that these areas were well-wooded. The resultant landscape was one of well-wooded lakesides and river valleys interspersed with large expanses of open savannah where the rain is more restricted and the heat is more intense. The savannahs included areas of bush and stands of some of the hardier trees, such as acacia. As the climate became more and more arid, they were increasingly dominated by C4 grasses which thrive in hot, dry conditions.

some of the hardier trees, such as acacia. Areas of forest are also documented. Samples taken from the former watercourses and the margins of the ancient lake include much more arboreal pollen, as much as 25%, indicating that these areas were well-wooded. The resultant landscape was one of well-wooded lakesides and river valleys interspersed with large expanses of open savannah where the rain is more restricted and the heat is more intense. The savannahs included areas of bush and stands of some of the hardier trees, such as acacia. As the climate became more and more arid, they were increasingly dominated by C4 grasses which thrive in hot, dry conditions.

Unfortunately, almost no pollen has been preserved in the volcanic deposits of the Laetoli region although some grass phytoliths have survived along with some fossil twigs and leaf impressions. Most of the evidence comes from the enormous collection of fossilized bone that has been collected and studied, and, of course, we also have the footprints of many of them. The Upper Laetolil Beds (Tuff 7) include the footprints made by an early australopithecine along with those at least twenty other animals and the corresponding fossilized remains have been found scattered through the region.

Ungulates

That fauna appears to have largely consisted of large ungulate grazers and browsers, many of them Bovidae (ancestral buffalo, cattle, gazelle and wildebeest), attracted by the expanding grasslands. Despite the lack of tree pollen, denser woodland is indicated by the large number of giraffid fossils found in the region and the presence of Suidae (pigs) such as Potamochoerus that prefer a forest environment. But the clincher is the number of non-hominin Primates present, mainly Old World Monkeys (Cercopithecidae), who would have fed on fruit and foliage and sought security in the treetops rather than in the open.

From the fossil remains, it would appear that browsers still outnumbered grazers during the Pliocene, but the gap was narrowing as the woodland shrank. The two groups can be easily distinguished by the general morphology of their teeth together with the wear pattern—eating grass tends to scratch the surface of the tooth while chewing leaves causes pitting. Impalas and long-necked giraffes continued to browse among the trees and several species of gazelle had a mixed diet. Many of the proboscideans, such as the deinotheres, stuck to a C3 browse diet while Anancus arvernensis, a gromphomere, showed an increased preference for grass. By the end of the period many of the ruminants that are currently found appear in the fossil record such as the wildebeest and greater kudu in south Africa. Also arriving were the early species of zebra along with various examples of antelope and kob.

The evolution of African predators. From left to right: Panthera leo, Acinonyx jubatus, Panthera pardus, Crocuta crocuta, Dinofelis, Hyaena hyaena, Megantereon cultridens & Homotherium latidens

Of course, all of this protein on the hoof attracted an array of predators and scavengers to take advantage. Certainly big cats, hyaenas, birds of prey and vultures are well attested. It was certainly a dangerous place to make a living and required a certain set of abilities and strategies to survive. Everything depended on access to water and this applied to the vegetation and those who fed on it, directly or indirectly. During the dry season, waterholes were vital to survival but also a source of a great deal of danger for the animals that gathered there. Without water and decent grazing, the older and younger members of the herd were weak and vulnerable. On the hand, a waterhole was the perfect place for an ambush.

Primates

Primates were among the animals that moved from the relative safety of the woodlands and into the plains, although none of the great apes were included among them. Chimpanzees and bonobos are mainly found in the Congo Basin while gorillas inhabit the forests of Rwanda, Uganda and the eastern part of the Democratic Republic of Congo. The migrants were all quadrupedal monkeys, such as baboons and geladas, whose forebearers had been tempted out of the treetops by the changing climate. They began to forage for fallen fruit and took to augmenting their diet with protein rich insects. As the savannah expanded, areas of woodland were more widely spaced on the landscape and it became necessary to cross open country in order to access isolated stands of fruit bearing trees.

Prominent among migrants were baboons and geladas who ventured out in groups of several dozen if not a hundred or more to forage around for fruit, seeds, the odd insect, and underground storage organs (rhizomes, tubers, etc.) and whatever else they might find. They relied on group defence to survive and it proved to be a highly successful strategy. With many pairs of eyes on the lookout, baboons today can generally spot a lion at up to about 100 metres, giving them ample time to scramble up a tree or a handy cliff face. But leopards are another matter. They are also adept tree climbers and are particularly dangerous at night, so the young and the sick and the elderly were always in danger.

Australopithecines

Members of the genus Australopithecus appear in Africa towards the end of the Pliocene—A. anamensis appearing in East Africa c. 4.2-3.8 million BP, A. afarensis about half a million years later, and A. africanus in South Africa at about the same time. It was a time of increased aridity and loss of habitat for forest dwelling primates. Woodlands with fruit bearing trees that made up the bulk of the ape diet tended to go dormant for long stretches of time, weeks or even months. Forested areas were spread further and further apart and the spaces in between came to be dominated by grasses. These were often difficult to digest at the best of times and provided very little nutrition in the dry season. Then, most of the plant’s carbohydrates were stored underground and required some effort to gather and a great deal of chewing and grinding to process. In the case of the flowering plants (‘forbs’) the ‘underground storage organs’ (USOs) took the form of bulbs or tubers while among the grasses theywere stored in rhizomes or corbs (swollen stems). These fall into category of what are known as‘fallback foods’, foods that are necessary to tide an animal over in times of scarcity. Of course, the plants themselves have not survived but the faunal record indicates that burrowing animals such as mole rats and porcupines that feed on them were present from the Miocene onwards. Carbon isotope and microwear analysis (pits, scratches, etc) of the teeth indicates that A. anamensis largely subsisted on C3 plants, which would indicate a mainly woodland habitat, but the dentition itself indicate important changes in the diet.The molars were larger with thicker enamel, and the canines were smaller than those of any of the apes.This new configuration was most likely a response to need to process fallback foods, which requires much more work than typical fare.

most of the plant’s carbohydrates were stored underground and required some effort to gather and a great deal of chewing and grinding to process. In the case of the flowering plants (‘forbs’) the ‘underground storage organs’ (USOs) took the form of bulbs or tubers while among the grasses theywere stored in rhizomes or corbs (swollen stems). These fall into category of what are known as‘fallback foods’, foods that are necessary to tide an animal over in times of scarcity. Of course, the plants themselves have not survived but the faunal record indicates that burrowing animals such as mole rats and porcupines that feed on them were present from the Miocene onwards. Carbon isotope and microwear analysis (pits, scratches, etc) of the teeth indicates that A. anamensis largely subsisted on C3 plants, which would indicate a mainly woodland habitat, but the dentition itself indicate important changes in the diet.The molars were larger with thicker enamel, and the canines were smaller than those of any of the apes.This new configuration was most likely a response to need to process fallback foods, which requires much more work than typical fare.

Isotope analysis of individual Au. afarensis fossils shows that some of them at least were consuming C4 plants either directly or by eating the flesh of grazing herbivores. It made up about 30-40% of the diet of Au. africanus in South Africa. In either case, it shows that they were moving out into the savannah. Animal protein most likely came in the form of scraps of flesh left over from carnivore kills or the carcasses of herbivores that had succumbed to old age or starvation. Fortunately, these events tended to take place during the dry season, when other foods were in short supply. Of course, there was intense competition from other scavengers—vultures, hyaenas or jackals—that were generally first on the scene but these were less active around midday, and generally retired to some shady spot to rest and repose. On occasions they might have needed fending off, possibly by chasing them off with sticks or throwing stones at them.

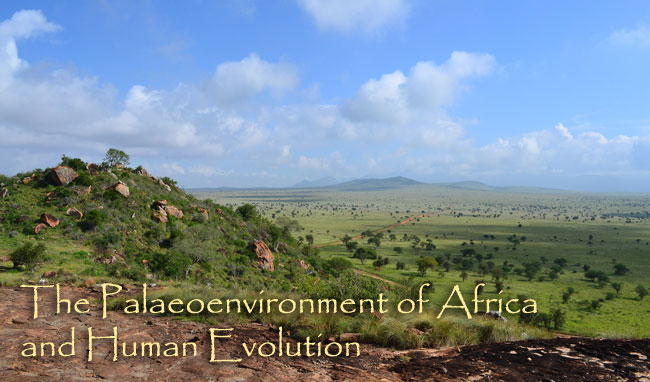

Other uses for stones were soon found. They could be used to smash and crack open bones to expose the highly nutritious marrow inside, which was generally overlooked by most predators and scavengers. The large-boned megaherbivores of the Pliocene would have provided far more marrow then is obtainable from the gazelles and antelopes of today. Their main competitors would have been hyaenas, but they generally operated at night. At some point, it was discovered that if two stones were bashed together they produced sharp edges that could be used to scrape the flesh from the bones. Exactly such  tools, simple though they might be, were discovered at Lomekwi on the west side Lake Turkana in Kenya in contexts dating to about 3.3 million years ago, and fossil bones from the same period, bearing the sort of cut marks associated with butchery have been found at Dikika in the Afar region of Ethiopia. An expansion of the frontal lobe of the australopithecine brain, the area that deals with abstract thought, language, planning, and the execution of motor skills, suggests they had the mental capacity to manufacture tools. In the absence of well-preserved fossil hands it remains to be seen whether they had the manual dexterity to do so.

tools, simple though they might be, were discovered at Lomekwi on the west side Lake Turkana in Kenya in contexts dating to about 3.3 million years ago, and fossil bones from the same period, bearing the sort of cut marks associated with butchery have been found at Dikika in the Afar region of Ethiopia. An expansion of the frontal lobe of the australopithecine brain, the area that deals with abstract thought, language, planning, and the execution of motor skills, suggests they had the mental capacity to manufacture tools. In the absence of well-preserved fossil hands it remains to be seen whether they had the manual dexterity to do so.

Finding food in the savannah meant covering much more territory than in the forest. Australopithecines had to be capable of walking longer distances in relative safety to acquire food and transport it to a secure location where they could process it and share it out. Good visibility was also helpful because danger lurked out in the tall grass and it was very useful to be able to spot it in time. Because of their ape ancestry, they had developed the ability to walk on their hind legs with an upright posture. An opposable big toe was a feature retained in at least some of the later australopithecines, as the Burtele foot would indicate. On the ground, an upright stature offered the benefits of greater visibility that an elevated viewpoint gives and, in addition, it freed the hands for carrying food back to the group or transporting infants. As the footprints found in the ash at Laetoli indicate, Au. afarensis had a much improved and more efficient way of getting about compared to Ardipithecus. Still, it wasn’t such that they could outrun predators so it was always advisable to stay close to some sort of refuge.

Further Reading

| Aronson, J. & M. Taieb | (1981) | “Geology and Paleogeography of the Hadar Hominid Site, Ethiopia”. In: Rapp G & Vondra CF, editors. Hominid Sites: Their Geologic Settings |

| Ayala, F.P & C.J. Cela-Conde | (2017) | Processes in Human Evolution. 2nd edition |

| Bonnefille, R. et al | (1987) | Palynology, stratigraphy and palaeoenvironment of a Pliocene hominid site (2.9-3.3 MY) at Hadar, Ethiopia. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 60 |

| Barham, L. & P. Mitchell | (2008) | The First Africans. African Archaeology from the Earliest Toolmakers to Most Recent Foragers |

| Cartmill, M. & F.H. Smith | (2022) | The Human Lineage.2nd edition |

| Clark, J. Grahame | (1969) | World Prehistory: A New Outline |

| Grine, F.E., J.G. Fleagle & R. Leakey | (2006) | The First Humans— Origin and Early Development of the Genus Homo |

| Harrison, T. | (2011) | “Laetoli Revisited: Renewed Paleontological and Geological Investigations at Localities on the Eyasi Plateau in Northern Tanzania”. In Paleontology and Geology of Laetoli: Human Evolution in Context: Volume 1. Edit. Terry Harrison |

| Lewen, Roger | (2005) | Human Evolution. 5th Edition. |

| Maslin, Mark | (2017) | Cradle of Humanity |

| Maslin, Mark, et. al. | (2014) | East African climate pulses and early human evolution. Quaternary Science Review. |

| Owen-Smith, Norman | (2021) | Only in Africa. The Ecology of Human Evolution |

| Rossouw L., & L. Scott | (2011) | Phytoliths and Pollen, the Microscopic Plant Remains in Pliocene Volcanic Sediments Around Laetoli, Tanzania. Paleontology and Geology of Laetoli: Human Evolution in Context. |

| Scarre, Cris edit | (2018) | The Human Past. 4th edition |

| Shea, John J. | (2017) | Stone Tools in Human Evolution |

| Su, D.F. & T. Harrison | (2007) | “The paleoecology of the Upper Laetolil Beds at Laetoli”. in Hominin Environments in the East African Pliocene: An Assessment of the Faunal Evidence. |

.jpg)

_fig._16.png)