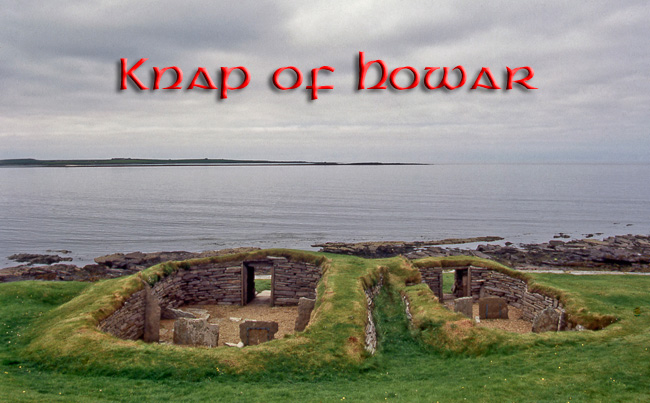

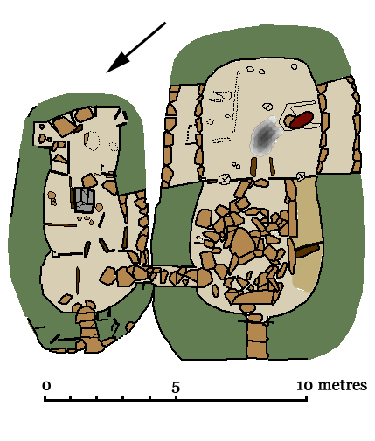

The oldest standing architecture found so far in Europe are on the remote island of Papa Westray, one of the Orkney Islands lying off the north coast of Scotland. The site, known as Knap o’ Howar (“knoll of mounds”) had been partially exposed by gales in the winter of 1928/29 and was excavated the following summer by William Traill, the landowner, and William Kirkness. They uncovered the remains of a pair of oblong buildings, one slightly larger than the other, linked together by a short passageway. They took the buildings to be Iron Age in date but more recent excavations by Anna Ritchie in the 1970’s have proved that they are many hundreds of years older than that and belong to the beginning of the  Neolithic period. A series of radiocarbon dates seemed to indicate that the site was occupied for about 900 years (ca. 3700-2800 BC). However, a more recent re-interpretation would lower the range by a third, to something like 3500-2900 BC.

Neolithic period. A series of radiocarbon dates seemed to indicate that the site was occupied for about 900 years (ca. 3700-2800 BC). However, a more recent re-interpretation would lower the range by a third, to something like 3500-2900 BC.

Ritchie’s work has also revealed that the existing buildings did not represent the earliest occupation of the site for there is an underlying midden layer 40 cm. thick. The midden consists of domestic refuse, including a lot of composted organic material but, apart from an area of paving to the south of House 1, no trace of any houses associated with it has been discovered. There are traces of wall foundations and paved areas between the houses and the sea but there has been considerable coastal erosion and any buildings that may have lay in that direction are now gone.

At Skara Brae on Mainland Orkney the buildings were also encased in midden material so there was undoubtedly a good reason for it. Fresh compost slowly breaks down to give off heat, and Saskatchewan farmers in bygone days used to heap manure and stall sweepings around their wood-frame houses to keep in snug during frigid prairie winters. Or perhaps they were hoping to take advantage of the same nutritive properties of the material that worked so well on their gardens and fields, thinking that by ‘planting’ themselves in fertilizer they too would thrive.

Both buildings were made out of stone, since trees have always been scarce in the islands while the local red sandstone readily splits into ready-to-use slabs. The walls consisted of an inner and outer skin of drystone with the cavity filled with more midden material. This technique may have been used to reduce the amount of labour involved or possibly to eliminate draughts but the resultant wall would have been far less stable than one that was solid stone. Interior space was sub-divided by upright stone slabs, the same method found in contemporary tombs (Orkney-Cromarty Tombs).

The standard interpretation is that the larger of the two was domestic in nature with living quarters at the front and a work area at the rear while the smaller was used as a workshop/storage area. However there is no reason why the former could function as a barn/byre for grain and livestock and the latter as living space.

House 1

House 1 (Photo ©Anna Ritchie)

House 1, the larger of the two, is a ‘waisted’ oblong in plan with rounded corners, and measures approximately 10 x 5 metres internally. Its walls are roughly 1.5 metres thick and 1.6 metres high. The  entrance is at the northwest end, facing the sea, and consists of a paved passage 1.7 metres long, with door checks and a stone sill at the inner end. At a point where the side walls pinch inwards slightly, the house was divided in two by a partition made up of thin stone slabs set on edge and a pair of timber posts. The tops of the outer pair of slabs were broken but the central pair survived intact and are only some 68 cm. high. This suggests that the aim was to mark a division rather than create a physical separation. The posts were chocked by small stones at the base and set between the slabs. They suggest a hipped roof, probably of thatch or turf. The outer room is about 26.5 square metres and had a floor that was at least partially paved. Along the south wall was a low platform about 18 cm. high, bounded by three long stone slabs laid flat and divided by a fourth, upright slab. The core was a mixture of stone and sand and the whole thing is generally supposed to have been a sleeping platform.

entrance is at the northwest end, facing the sea, and consists of a paved passage 1.7 metres long, with door checks and a stone sill at the inner end. At a point where the side walls pinch inwards slightly, the house was divided in two by a partition made up of thin stone slabs set on edge and a pair of timber posts. The tops of the outer pair of slabs were broken but the central pair survived intact and are only some 68 cm. high. This suggests that the aim was to mark a division rather than create a physical separation. The posts were chocked by small stones at the base and set between the slabs. They suggest a hipped roof, probably of thatch or turf. The outer room is about 26.5 square metres and had a floor that was at least partially paved. Along the south wall was a low platform about 18 cm. high, bounded by three long stone slabs laid flat and divided by a fourth, upright slab. The core was a mixture of stone and sand and the whole thing is generally supposed to have been a sleeping platform.

A pair of recumbent stone slabs marked the entrance to the inner room, which is slightly smaller, a little under 21 metres square, and had a bare earthen floor. Traill and Kirkness were  primarily interested in the architecture and did not pay to much attention to the small flint artefacts and broken pottery that came from the floor deposits.

primarily interested in the architecture and did not pay to much attention to the small flint artefacts and broken pottery that came from the floor deposits.

The front room was almost entirely cleared out and the finds unrecorded when Ritchie came to work on the site but she found 2 cm. of deposit in the back room. There was a central hearth (an ash filled hollow). A large quern was found next to the hearth, along with two grinding stones and some broken razor shells (ground shell was used as temper in the pottery found at the site). There are some grooves in the clay floor on the northern side of the room that Ritchie believes may represent bedding slots for a wooden bench. A small hollow to the north of the hearth contained a small, crude pot and was covered over by a large rim sherd. Ritchie is of the opinion that, based on the material evidence (no matter how imperfectly recovered) the front room was living quarters while the back room was a work area.

House 2

House 2 (Photo ©Anna Ritchie)

At the point where the two buildings abut, a connecting passageway about 2½ metres long led from House 1 to House 2. The door checks were at the far end of the passage, where it enters House 2, leading some to believe that it was the earlier  building but this is, at best, speculative. It is somewhat smaller, about 7½ x 3 metres, and less substantial. The walls, which survive to a height of 1.26 metres, are only about a metre or so thick. The main entrance was to the west, facing the sea, and was a short passage about 1.3 metres long and 60 cm. wide.

building but this is, at best, speculative. It is somewhat smaller, about 7½ x 3 metres, and less substantial. The walls, which survive to a height of 1.26 metres, are only about a metre or so thick. The main entrance was to the west, facing the sea, and was a short passage about 1.3 metres long and 60 cm. wide.

The interior is divided into three rooms by partitions similar to the one in House 1—in this case the walls are ‘pinched’ in two places. The outer room was pretty much featureless but the inner two may have functioned as work and storage areas, although this is purely speculative. The central room contained two successive hearths and floor deposits some 20 cm. thick, rich in organic material with pottery and tools of flint and bone.

There are two recesses in the south wall with a rough stone bench on the opposite side of the hearth. There were grooves in the ground surface underlying the bench  that may mark where a wooden version once stood. Two grinding stones were found on top of the bench The innermost room primarily used for storage—it was provided with three recesses and five cupboards made out of upright slabs and stone lintels. There were two small pits in the floor of the innermost compartment, one was probably a post hole but the other was covered by a stone slab and contained animal bones along with a hammer stone. Otherwise, the room had been pretty thoroughly emptied in the 1920’s.

that may mark where a wooden version once stood. Two grinding stones were found on top of the bench The innermost room primarily used for storage—it was provided with three recesses and five cupboards made out of upright slabs and stone lintels. There were two small pits in the floor of the innermost compartment, one was probably a post hole but the other was covered by a stone slab and contained animal bones along with a hammer stone. Otherwise, the room had been pretty thoroughly emptied in the 1920’s.

In the end, the doorway to House 2 was blocked up, as was doorway at the end of the passage linking it to House 1. The rest of the passage was apparently left clear and probably used as a storage area. The blocking may have been because the building was unstable and prone to collapse owing to the thinness of its walls, which were further weakened by the provision of so many recesses. House 1 apparently continued to be occupied for a time before eventually being abandoned.

Domestic Economy

Outside the houses was an extensive spread of midden deposit covering about 35 cm. thick and covering an area of 500 square metres. The lower level of midden antedates the buildings while the upper level is associated with them. The content was pretty much the same in both with plenty of artefacts and organic material. Apart from a few carbonized grains of barley  and some wheat pollen, there was not much in the way of plant material.

and some wheat pollen, there was not much in the way of plant material.

The bones of domestic cattle and sheep were plentiful and in roughly equal proportions. The cattle were apparently quite large and not far removed from the wild aurochs. The sheep were also in an early stage of domestication and were probably raised for meat rather than their meagre wool. The young age at which the animals were killed seems to confirm this. Fish bones were plentiful and analysis has shown that they belong to both inshore and offshore varieties. There was also plenty of shell—mainly limpet, which is only really useful as bait, but also including some more digestible such as oyster, winkles and cockles. The shells were also ground up to use as a tempering agent in pottery.

Material Culture

As far as cultural material is concerned, a good deal of flint and chert was recovered from the midden, including a few knife blades and scrapers. The raw material presumably came from nodules that washed up on the beach. Ground stone tools include a polished axe, borers as well as grinding equipment to process grain among other things. There were bone items—needles, awls, spatulas and the like—and fragments of at least 78 different pots. These were mostly bowls and storage jars, generally round-bottomed and plain, but a few were decorated in the so-called Unstan style and probably served as tableware.

Disposal of the Dead

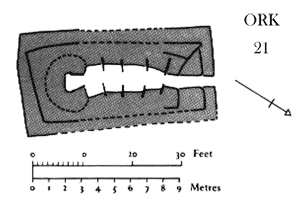

Tombs containing Unstan Ware have been found throughout the islands and it would be strange not to find one for the use of the people at Knap of Howar. The type is known as a stalled cairn, so called because the interior is divided by partition walls, just like  a stable or a byre, to create two rows of stalls. They share some of the same building techniques as the houses— the use of stone partitions being most obvious.

a stable or a byre, to create two rows of stalls. They share some of the same building techniques as the houses— the use of stone partitions being most obvious.

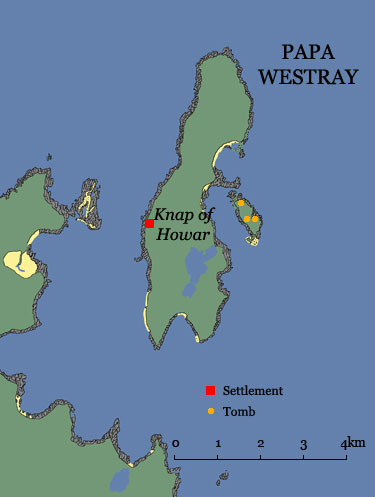

No tombs have been discovered on Papa Westray itself but there are the remains of three on the small islet known as the Holm of Papa Westray, which lies off the east side of the island. The northern tomb is a stalled cairn, in its final form at any rate. It has four pairs of stalls and a terminal chamber at the south end. Of course, there is no way of linking this particular tomb directly with Knap of Howar but the Holm may well have been joined to the rest of the island at the time. Or perhaps there was a more conveniently located tomb that has since disappeared.

Reference

The principal source of information on Knap of Howar is Anna Ritchie's report (Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, 113 [1983]).