During the last Ice Age (ca. 70,000-10,000 BC), huge ice sheets covered almost all of the British Isles making them pretty much uninhabitable— certainly this was the case in Scotland. Further south, however, the summer grazing was available in the lowlands of what is now south-eastern England. The huge amount of water locked up in the polar ice caps and immense glaciers that covered much of the northern hemisphere. Consequently, sea levels were much lower than today’s and large herds of migratory animals, such as reindeer, were able to move across the dry North Sea bed to take advantage. Upper Palaeolithic artefacts dredged up from the sea bed show that human hunters were in hot pursuit but whether they actually made it to what is now Britain is an open question.

Global warming, when it finally came, made Britain a much more hospitable place and, since it was still connected to the continent, it was wide open to colonization by plants and animals (including people). By  the 9th millennium BC, the lowlands and much of the highlands were covered by forests. These were full of game but, unlike the reindeer and bison of the previous era, they did not travel in large herds along predictable routes that left them open to ambush, but tended to be more solitary and elusive. Even so, in terms of bio-density, they provided much more meat per given area and people soon moved in. A wide variety of plant resources, including nuts, berries, fungi, tubers and edible roots were also readily available among the trees.

the 9th millennium BC, the lowlands and much of the highlands were covered by forests. These were full of game but, unlike the reindeer and bison of the previous era, they did not travel in large herds along predictable routes that left them open to ambush, but tended to be more solitary and elusive. Even so, in terms of bio-density, they provided much more meat per given area and people soon moved in. A wide variety of plant resources, including nuts, berries, fungi, tubers and edible roots were also readily available among the trees.

Other environments had similar concentrations of resources, among them the coastal areas of western Scotland and the Hebrides. The Atlantic cliffs were the breeding grounds for millions of seabirds, which (along with their eggs) have been a mainstay of the local diet right down to the last century. All sorts of different species of molluscs can be found in the intertidal zone or just offshore, and huge shell middens, representing hundreds of occupations, have been excavated on the small island of Oronsay in the Inner Hebrides.

Fish bones were present, 90% of which were deepwater fish that would certainly have required boats. The remains of various sea mammals, especially seals and otters, were found and, as well as meat, they provided fur for clothing, stitched together with sinew. There were deer on the hillsides and wild boar in the forests, along with salmon and trout in the streams. The Haida and Nootka of the Pacific coast of Canada lived in a very similar environment and were able to establish permanent settlements based on this type of economy. Like them, the early inhabitants of the west coast of Scotland would have had to be skilled boatmen, plying the coastal waters and open seas in craft that were probably not much different than the leather curraghs of Ireland. This type of boat is relatively easy to make, lightweight yet very sturdy. However, given the materials involved, they are unlikely to have left much if any trace in the archaeological record.

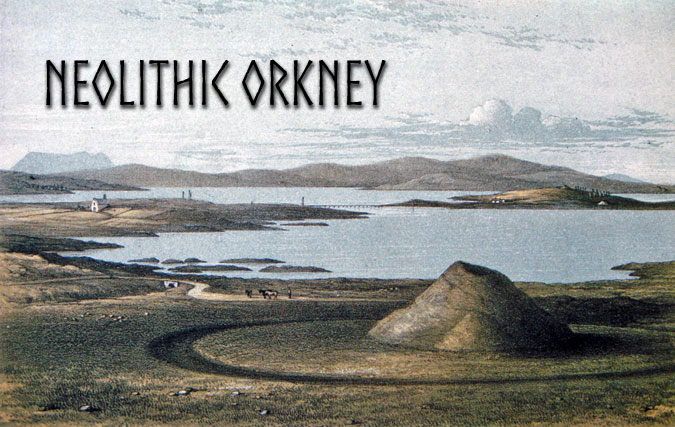

Looking across the Pentland Firth to Hoy

About six thousand years ago a new and radically different means of subsistence, agriculture, made its first appearance in Britain and quickly spread throughout the British Isles. It was based on the cultivation and harvesting of cereal crops, wheat or barley, and the herding of livestock— some combination of sheep, goats and cattle. None of these, neither the plants nor the animals, were native species but had originated in what we now call the Middle East some four or five thousand years earlier. From there, the new economic package quickly spread from the Balkans throughout Europe, eventually reaching Britain by about 4000 BC.

By that time the land link to the continent had been flooded by rising sea levels, so the plants and animals must have been transported across the Channel or over the North Sea by boat. One question that troubles prehistorians is whether they were acquired by natives through contact with the continent or were they brought by newcomers— or perhaps a bit of both? The latest evidence, based on genetics, suggests they were brought by colonists but there is still some debate. In any case, the new lifestyle spread rapidly and within a century or two at most farming had arrived in the Orkney Islands, in the far north of Scotland.

Orkney

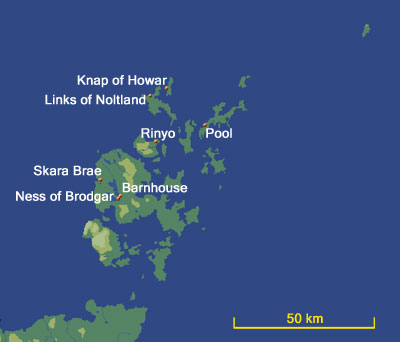

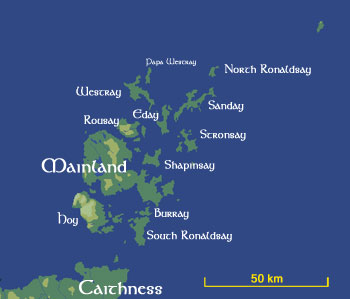

Geographically, the Orkney archipelago is a continuation of Caithness, cut off by rising waters during the last great glacial melt about ten thousand years ago. There are about 70 islands altogether— mainly low-lying, apart from some steep hills on Hoy and  rugged cliffs on the western side of the larger islands.

rugged cliffs on the western side of the larger islands.

Orkney is very much a watery world and, before the development of paved roads, communication was primarily by water and settlements tended to be located on the shore. Pollen and charcoal samples from a number of sites indicate that the earliest farmers encountered an landscape that was covered by mixed birch-hazel woodland but that this had given way to an open, grassy environment by the Late Neolithic. This was no doubt the result of land clearance for agriculture and the felling of trees for fuel and structural purposes. The underlying rock is mainly Old Red Sandstone, which occurs as well-bedded flagstones, fairly easy to split off and an ideal building material once the trees had disappeared.

The surrounding seas are tempestuous but were rich in resources. The cliffs surrounding them were breeding grounds for vast numbers of seabirds, and large colonies of seals populated the beaches. The beaching of pods of whales or dolphins was a regular occurrence, as demonstrated by the recent discovery of about a dozen bodies that had been buried on the beach at Cata Sands on Sanday in the early nineteenth century.

The Early Neolithic: The First Farmers

The distance from Caithness is relatively short, only a few kilometres, but the intervening stretch of sea— the Pentland Firth— is one of the most treacherous in the world. Violent tidal races flow from the North Sea, colliding with those from the Atlantic, and gale force winds are a regular occurrence. Crossing it in small open boats would be perilous at the best of times but having to transport livestock and seed corn would have been an enormous gamble, especially if you had to deal with cattle that were not that far removed from the wild and weighed over a ton and a half when fully grown. It was long thought this was purely a process of colonization and that the islands had been unoccupied up to that point. But recent surveys have turned up typical Mesolithic flintwork, so it is possible that local adoption played a role.

The Cliffs at Yesnaby with Hoy in the background

The earliest sites are characterized by a particular type of pottery known as Unstan Ware, after the tomb where it was first identified. It is a coarse-tempered ware derived from the Carinated Bowl tradition and is  characterized by shallow bowls with rounded bottoms, a carinated profile and rims bearing simple patterns of incised or impressed decoration.

characterized by shallow bowls with rounded bottoms, a carinated profile and rims bearing simple patterns of incised or impressed decoration.

Until quite recently, the only early neolithic site to be completely excavated is Knap of Howar (left) on Papa Westray, one of the smaller outlying islands to the north and therefore probably not among first places to be settled. Since its excavation in the 1980s, evidence for earlier timber structures has been discovered at a number of sites in Orkney, which has caused archaeologists to re-evaluate their thinking— something archaeologists are not always happy to do. The surviving buildings are not even the earliest on the site. Although they were lived in for perhaps as long as six centuries according to the latest estimates, from as early as 3500 until about 2900 BC, they were set in a deposit of midden material which must have come from an earlier occupation, perhaps timber-built, although so far no trace has been found.

The site, which appears to be a single dwelling homestead, does not look very much different to the black-houses that were the standard rural dwelling along the west coast and in the Hebrides well into the twentieth century. These consisted of a pair of oblong buildings linked by a short passage— a dwelling place with a workshop/storeroom attached. A large number of bones from cattle and sheep were found, along with plenty of shell and fishbone but virtually nothing in the way of grain and little evidence of grinding. It would seem reasonable to assume that the people who lived here were not isolated, but part of a more extensive community with each household specializing to some degree and sharing the wealth around in some sort of reciprocal relationship, based on family ties.

The Late Neolithic: Megalithic Orkney

The settlement of Skara Brae (ca. 3200-2300 BC), on the west coast of Mainland (the largest island of the group), is much bigger and much better known (below left). It was excavated by Vere Gordon Childe, one of the leading archaeological lights of the 1930s and 40s, who uncovered a very well- preserved, semi-subterranean village consisting of a cluster of houses connected by a network of tunnels. Each house was furnished with a central hearth, box beds and a stone dresser, presenting a rather cozy picture of community living.

preserved, semi-subterranean village consisting of a cluster of houses connected by a network of tunnels. Each house was furnished with a central hearth, box beds and a stone dresser, presenting a rather cozy picture of community living.

There is a good deal of similarity between Skara Brae and Knap of Howar, particularly in the architecture and ceramics of the earliest occupation. However, the Unstan Ware found in the earliest houses at Skara Brae eventually gave way to Grooved Ware, a pottery style that is also associated with the henges and stone circles constructed at at Stenness and Brodgar. Grooved Ware also characterizes the rather specialized villages at Barnhouse and Ness of Brodgar, which are located in close proximity to the two circles (see below). It is clear from the recent excavations at Pool (Sanday) that the two styles overlapped for a considerable period and did not represent two distinct waves of immigration, as had long been thought.

Looking across Eynhallow Sound to Rousay and Westray

Death and the Afterlife

The presence of so many communal tombs in the islands suggests profound, otherworldly beliefs, perhaps even a notion of the afterlife. We are only beginning to come to grips with the variety and sophistication of beliefs and practices these monuments represent. There are essentially two types of tomb in Orkney— the so-called Orkney-Cromarty and Maes Howe types. They too can be distinguished by their pottery with Unstan Ware associated with the former and Grooved Ware with the latter. However, the latest dating evidence would seem to indicate that, for the earlier part of the Neolithic (ca. 3500-2900 BC), they were contemporary and only in the third millennium BC did Orkney-Cromaty tombs fall out of use.

Knowe of Yarso, Rousay

As was the case elsewhere in Europe, the inhabitants erected chambered tombs to serve as repositories for the bones of their ancestors and to mark their territory. Through these relics they could summon the spirits of their ancestors to give them guidance and approval. They could intercede on the family’s behalf with the external forces that controlled their lives.

There are many more tombs of the Orkney-Cromarty type and it seems likely that each was used by a single, small community— perhaps just a family farmstead. Building them did not require a huge amount of labour and the architectural principals and techniques were much the same as those used in their houses. Maes Howe-type tombs, on the other hand, are comparatively thin on the ground and required a great deal of effort to build. The internal masonry is very precise and the overall bulk of the tombs are much greater. While the earlier tombs were simply meant to be seen, these were intended to dominate the landscape. They signify a more complex society, able to draw resources— both material and human— from a wider area.

Art

The decorative arts were certainly flourishing by the time of Skara Brae and in a number of different media. Elaborately and laboriously carved portable stone objects (such as these examples from Skara Brae, right) have been found in what otherwise appear to have been dwelling places. These obviously had a lot of meaning to the inhabitants, but we can only guess as to exactly what that was. The most obvious interpretation is that they were symbols of power— religious, political or a combination of both— but there are many other, equally plausible explanations.

The decorative arts were certainly flourishing by the time of Skara Brae and in a number of different media. Elaborately and laboriously carved portable stone objects (such as these examples from Skara Brae, right) have been found in what otherwise appear to have been dwelling places. These obviously had a lot of meaning to the inhabitants, but we can only guess as to exactly what that was. The most obvious interpretation is that they were symbols of power— religious, political or a combination of both— but there are many other, equally plausible explanations.

Representations of humans or animals, which were fairly common elsewhere in Europe and the Near East at about the same time, are rarely found in the British Isles but two of them have been found in Orkney, including the so-called Westray Wife, found at Links of Noltland in 2009, and the Brodgar Boy (left, ©ORCA) found at the Ness of Brodgar a year later.

Representations of humans or animals, which were fairly common elsewhere in Europe and the Near East at about the same time, are rarely found in the British Isles but two of them have been found in Orkney, including the so-called Westray Wife, found at Links of Noltland in 2009, and the Brodgar Boy (left, ©ORCA) found at the Ness of Brodgar a year later.

The walls of their dwellings and tombs were often carved with reliefs in geometric and curvilinear patterns, such as that found on a stone slab found at Pierowall on Westray, the latter resembling designs found as far away as the tomb of Newgrange in Ireland. Hundreds of examples of decorated stones have been uncovered at the ongoing excavations at the Ness of Brodgar and many more will undoubtedly appear in subsequent seasons. Their sheer quantity for the first time gives art historians a real chance of at least beginning to understand their meaning

Maes Howe from the North-east. Note the bank and ditch of the surrounding henge.

Ceremony

During the later part of the Neolithic, the British Isles was characterized by stone circles, large and small along with a host of smaller stone settings and individual standing stones (orthostats in archaeo-speak).  However, nowhere was there such a concentration of these as that part of the main island known as the Heart of Neolithic Orkney, which is set in a natural amphitheatre of low hills encompassing a pair of lochs— one freshwater (Loch Harray) and the other salt (Loch Stenness)— separated by a narrow isthmus. At either end of the isthmus, about 1.5km apart, are two great stone circles, the Stones of Stenness (left) to the south-east and the Ring of Brodgar to the north-west. Both of them are ‘henge’ monuments, that is to say they are defined by ditch with an external bank.

However, nowhere was there such a concentration of these as that part of the main island known as the Heart of Neolithic Orkney, which is set in a natural amphitheatre of low hills encompassing a pair of lochs— one freshwater (Loch Harray) and the other salt (Loch Stenness)— separated by a narrow isthmus. At either end of the isthmus, about 1.5km apart, are two great stone circles, the Stones of Stenness (left) to the south-east and the Ring of Brodgar to the north-west. Both of them are ‘henge’ monuments, that is to say they are defined by ditch with an external bank.

However, there are two other sizeable henges in the immediate vicinity that must be taken into account—the Ring of Bookan, which lies about a mile to the northwest of Brodgar. This is just about the same distance as separates Brodgar and Stenness and all three are in rough alignment. In addition there is the great chambered tomb at Maes Howe, which sits in the middle of what is essentially a henge that clearly pre-dates it.

Associated with this complex is the contemporary collection of buildings at Barnhouse which lies barely 50m from the Stones of Stenness. Excavated in the late 1980s, the site consists of a number of structures with unusual features including a large oblong building with an outer wall and a hearth in the entrance passage. It is thought that the site may have been home to a community of priests who were responsible for looking after the nearby monuments.

However, just as prehistorians were getting to grips with this new development, a new site appeared that changes everything— the Ness of Brodgar. As its name indicates, it is located at the tip of the promontory that leads down to the Isthmus of Brodgar. Since its discovery in 2003 it has been subject to continuous annual excavations and the results have been staggering. Barely one-tenth of the site has been dug but already a number of very intriguing structures have been found, surrounded by an enormous enclosure wall 4m thick. Establishing the relationship between this settlement and the monuments surrounding it will be an enormous challenge.

The End of the Neolithic

From early in the third millennium BC until near its end, Orkney was one of the premier centres of Neolithic culture in the British Isles, if not the pre-eminent one (according to the BBC). By about 2100 BC, however, the settlement at Skara Brae was abandoned and the great tombs such as Maes Howe were finally sealed. At the Ness of Brodgar, an enormous feast was held, involving the slaughter of hundreds of cattle, after which the site was buried under hundreds of tons of midden (compost) material and abandoned. The Early Bronze Age period that followed was, by all appearances, impoverished by comparison— no monumental tombs nor elaborate stone circles were built and settlement was relatively thin on the ground. The explanation for all of this is one of those ‘big questions’ that archaeologists love.

Suggested Reading

| Card, Nick | (2011) | Ness of Brodgar, Stenness, Orkney Excavations 2011 Data Structure Report, ORCA 271. |

| Davidson, A.L. & A.S. Henshall | (1989) | The Chambered Cairns of Orkney |

| Garnham, Trevor | (2004) | Lines on the Landscape, Circles from the Sky |

| Renfrew, Colin (ed.) | (1985) | Prehistoric Orkney |

| Richards, C. (ed.) | (2005) | Dwelling among the Monuments |

| (2013) | Building the Great Stone Circles of the North | |

| Richards, Colin & Richard Jones (ed.) | (2016) | The Development of Neolithic House Societies in Orkney |

| Wickham-Jones, C. | (2006) | Between the Wind and the Water. World Heritage Orkney |

Internet Resources