The Royal Apartments

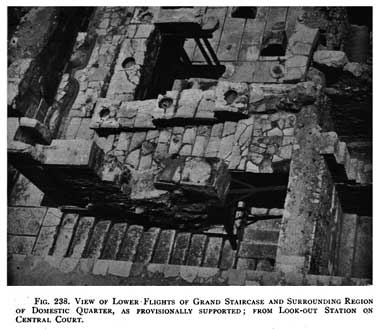

Grand Staircase

The ground slopes away rather quickly on the eastern side of the site and the builders had to cut away part of the side of the hill to accommodate the buildings. Most of what survives is actually one or two floors below the level of the Central Court. How high the buildings rose above the court is unknown but it is clear from Evans excavations that there must have been at least one storey.

the buildings. Most of what survives is actually one or two floors below the level of the Central Court. How high the buildings rose above the court is unknown but it is clear from Evans excavations that there must have been at least one storey.

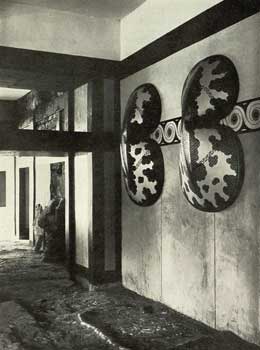

The Grand Staircase is located at about the middle of the east side of the Central Court and presumably was entered from it (although no trace of an opening has survived). There were at least five flights of broad, gypsum stairs, the lowest two resting on solid earth and the others on wooden beams supported by wooden columns. There was a light-well immediately adjacent on the east, which opened onto a lobby, the Hall of the Colonnades (opposite right), on each of the lower floors. The walls were decorated with painted murals including bands of running spirals—superimposed by full-sized replicas of the characteristic Minoan ‘figure eight’ shields in the case of the upper hall. As well as practical weapons of war, such shields were evidently powerful religious symbols representing the Young God. The staircase was heavily restored by Evans but, in large part, this was done for structural reasons to replace the wooden columns, which had long since rotted away, with concrete versions.

case of the upper hall. As well as practical weapons of war, such shields were evidently powerful religious symbols representing the Young God. The staircase was heavily restored by Evans but, in large part, this was done for structural reasons to replace the wooden columns, which had long since rotted away, with concrete versions.

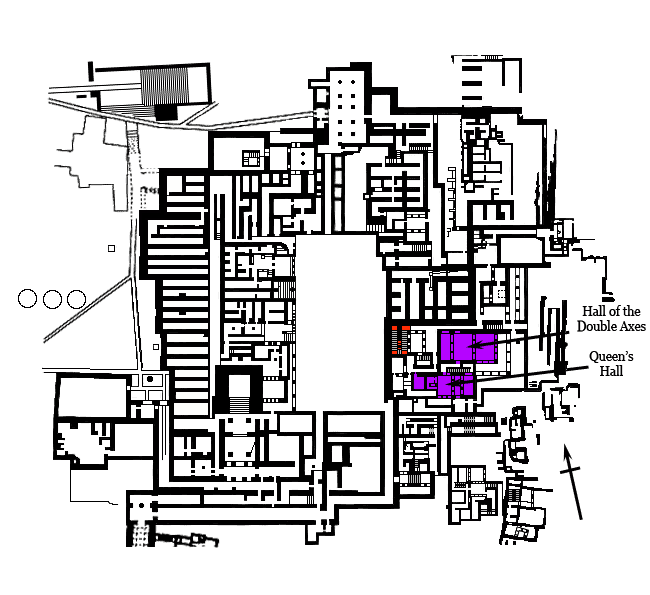

From the lower landing, the Lower East-West Corridor leads to what Evans believed were the Domestic Apartments of the palace. These consisted of two suites, the Hall of the Double Axes and the Queen's Hall, spread over at least two storeys and linked by a series of corridors and stairways. They were equipped with light-wells and polythyra to open up or close down the rooms.

The Hall of the Double Axes

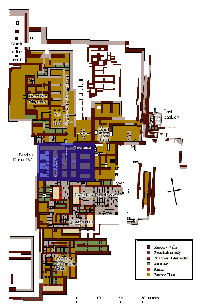

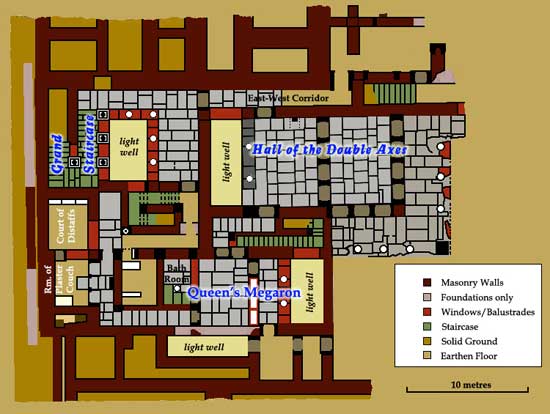

Plan of the Domestic Apartments

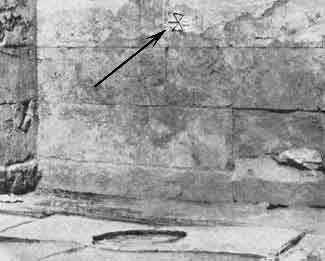

The Hall of the Double Axes got its name from the crude axe symbols (labrys) carved on the walls of the light well at the west end. The suite consists of a large rectangular room, sub-divided by a polythyron with four doors, and a portico which overlooked the valley of the Kairatos to the east. The layout is quite distinctive and occurs at the other palace sites as well. Evans suggested that it suited the domestic requirements of the king and queen. However, this interpretation is largely based on the fact that he could find no alternative arrangements that might be used for their private quarters anywhere else in the palace. Clearly they had to sleep somewhere but would they really want quarters that were so open to the elements and lacking in privacy?

Hall of the Double Axes. Portico

A more recent interpretation is that these suites were used for ritual purposes, something that involved moving between total darkness and the light through the use of the multiple doors. This is the sort of thing (sensory deprivation) that is quite common in rites of passage, the sort of initiation ceremonies that mark the transition between adolescence and adulthood.

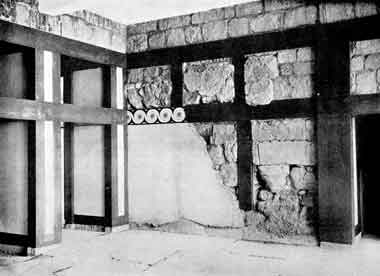

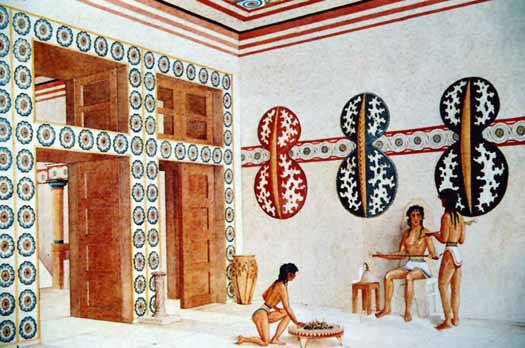

Audience Chamber of the Hall of the Double Axes

In the western part of the main room, or Audience Chamber as Evans called it, he found a mass of lime heaped against the north wall. Preserved in lime was the cast of a large wooden object along with those of a pair of fluted columns, one on each side. Presumably they represented the remains of a wooden throne (the outline of the lower part of the seat survives) and a canopy. The room was divided into two, roughly equal, halves by a quadruple polythyron. Evans believed that there may well have been transom windows above each door and that is how they have been restored, but there is no clear evidence to support this assumption.

The walls were decorated with a band of rosettes and running spirals, similar to that found in the Hall of the Colonnades but without the shields. In Evans’ opinion that was because actual shields were hung in their place.

Restored interior view of the Hall of the Double Axes (watercolour by Piet de Jong)

To the south and east were other polythyra that opened onto and L-shaped portico and a small courtyard, also L-shaped. The courtyard was enclosed by walls on the southern and eastern sides with a doorway in the southwest corner connecting it to the Queen’s Megaron and another near the northwest corner giving access to a stairway that descends to the Eastern Terraces.

The Queen’s Apartments

Restoration of the the north end of the Queen’s Megaron showing the entrances to the dog-legged passage (left) and the stairway to the upper floor (right). Photo by Chris 73 at Wikimedia Commons

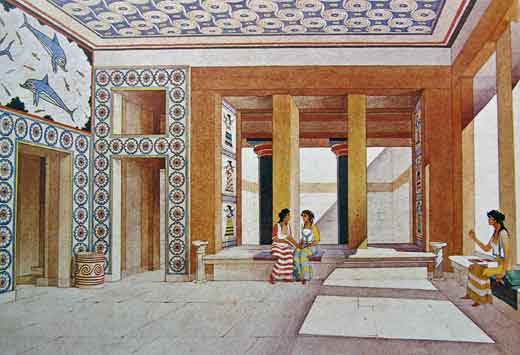

A dog-legged passage led from the Hall of the Double Axes to a smaller version that Evans dubbed the Queen’s Megaron. In this case, instead of a series of doors, the hall was sub-divided by a low stylobate about 38 cm high, supporting a pair of pillars. On top of the gypsum blocks that made up the stylobate, Evans found carbonized wood with a coating of plaster leading him to believe that it  was used as a bench, one whose height he believed was designed to accommodate women rather than men. At the north end of the bench is a doorway, linking the room to a sort of portico with a light-well beyond.

was used as a bench, one whose height he believed was designed to accommodate women rather than men. At the north end of the bench is a doorway, linking the room to a sort of portico with a light-well beyond.

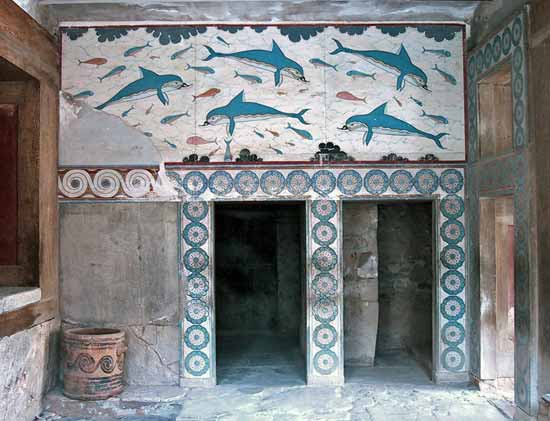

Fresco fragments depicting a woman with long, wavy tresses were found in the light-well (right).Her hair hangs rather limply down to her neck but then seem to fly out from her shoulders. Evans thought she was spinning around as she danced but the attitude of the  rest of her body does not seem to support this. It may well be that she is a goddess, descending from heaven, a scene that is often depicted on seals. The size and scale of the figure suggested to Evans that it belonged on the side panel of one of the pillars. He also found fragments of tunny and two swimming dolphins (left), restored versions of which were placed over the door on the north side of the room by Piet de Jong in the course of his restorations. However, many scholars now believe they originally decorated the floor of the room above.

rest of her body does not seem to support this. It may well be that she is a goddess, descending from heaven, a scene that is often depicted on seals. The size and scale of the figure suggested to Evans that it belonged on the side panel of one of the pillars. He also found fragments of tunny and two swimming dolphins (left), restored versions of which were placed over the door on the north side of the room by Piet de Jong in the course of his restorations. However, many scholars now believe they originally decorated the floor of the room above.

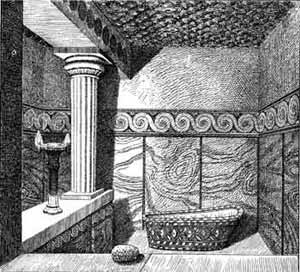

Reconstruction of the Queen's Hall (watercolour by Piet de Jong)

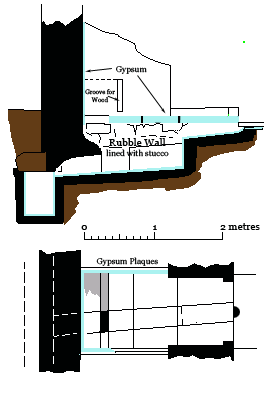

At the north end of the hall was a balustrade, separating it from a small bathroom. The balustrade actually turns inwards next to the door and it was there that Evans found a painted clay tub that  enabled him to identify the function of the room. The walls were lined with gypsum and the floor was paved with the same material—not the ideal waterproofing.

enabled him to identify the function of the room. The walls were lined with gypsum and the floor was paved with the same material—not the ideal waterproofing.

There was a corridor next to the bathroom door that led to what Evans described as a “toilette” and which he named the Room of the Plaster Couch because of the oblong plaster dais found in the southwest corner. A narrow closet projects from the east wall of this room, which contains what Evans believed was a latrine. There were grooves in the wall to hold a wooden seat about 57 cm above the floor.

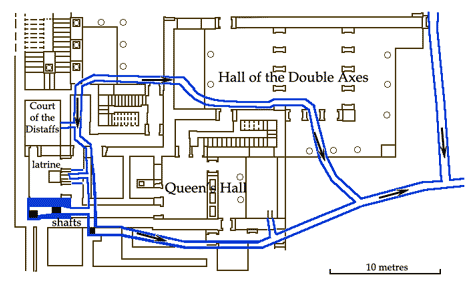

An opening beneath the seat connected by means of a vented drain to the main sewage system for this part of the palace. This consisted of a cement-lined conduit about 78 cm high and 38 cm across that ran in a circuit around domestic quarter, from a high point by the Grand Staircase. Shafts in a block of masonry next to the Room of the Plaster Couch fed effluent from the upper floors.

Plan of the Drains in the Domestic Apartments

Illumination in this part of the wing was provided by a small light-well, known as the Court of the Distaffs from the symbols carved on its walls. From the northeast corner of the Room of the Plaster Couch, a corridor led to another private staircase leading to the upper chambers before ending up in the Hall of the Colonnades once again.

Unless otherwise stated, all black & white photos of Knossos are from The Palace of Minos by Arthur Evans and are reproduced here courtesy of the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford University